Male Factor: Sperm Quality and Diet

A healthy pregnancy requires at least one healthy egg to be present in the company of at least one (but usually millions) of healthy sperm. A semen analysis is usually the screening test used to check for evidence of “male factor” infertility, i.e. some deficiency in the quantity or quality of sperm that may be contributing to a couple’s difficulty conceiving. In at least 30-40% of couples undergoing evaluation for infertility, a semen analysis will reveal some abnormality in at least one of the major categories by which we judge sperm: concentration (how many), motility (what percentage of the sperm are swimming properly), and morphology (what percentage of the sperm have a normal shape).

The task of deciding whether or not the semen analysis is “normal” may seem simple, but in reality it is often hardly clear-cut. For one thing, a man’s sperm parameters can change on a daily basis, so one borderline normal or abnormal result may not tell the whole story. For this reason, a fertility specialist will sometimes request the male partner to produce a second sample before deciding whether or not a man has a meaningful abnormality. Many specialists will recommend a 6-10 week waiting period before repeating the semen analysis. This is because the “life cycle” of a man’s sperm is approximately 60-80 days, such that two abnormal semen analyses spaced by this much time provides stronger evidence of a “true” (i.e. persistent, as opposed to transient) problem.

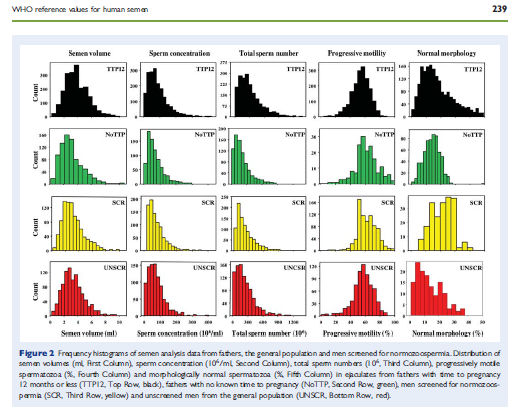

While severe male factor infertility is uncommon and is usually caused by an identifiable/specific medical condition (e.g. genetic, hormonal, anatomic, etc.), more mild sperm issues are quite common and often have no specific explanation. In fact, in men with more minor abnormalities, it can be unclear as to whether the semen analysis represents a real explanation for infertility at all, as the boundaries between normal and abnormal are chosen using math and statistics, but they change over time and don’t correspond specifically to any biological process or condition (the World Health Organization reference values are the ones most commonly used; they last underwent a major update in 2010).

The lack of an explanation/reason for the problem can be frustrating for couples with mild male factor infertility. Only a few lifestyle issues have been clearly shown to be important, such as smoking, marijuana use, and steroid use. A couple of recent studies have tried to find a relationship between a man’s diet and his semen analysis. In one study, a relatively weak association was found between high total dietary fat intake and low sperm concentration and motility; this relationship was driven in large part by saturated fat in particular. In another study, men consuming an overall healthier diet had very slightly better sperm motility, but no difference in concentration or morphology.

Like many studies looking at dietary issues, these studies used diet questionnaires, which are notoriously unreliable. Furthermore, the associations the studies found were slight and their true significance is questionable. While both studies suggested the possibility of an association between a healthier diet and better sperm counts, the role of diet and nutrition in male factor infertility is far from certain and needs further, and more rigorous, investigation.

References:

1. Attaman et al. Human Reproduction 2012 May;27(5):1466-74. Epub 2012 Mar 13.

2. Gaskins et al. Human Reproduction 2012 Aug 11. [Epub ahead of print]

Joshua U. Klein, MD

Joshua U. Klein, MD